So far in our posts for Disability History Month and focusing on the Great Eastern Railway’s benevolent fund book (see here and here) we’ve looked at the accidents and some of the aids and ‘remedies’ that were put in place afterwards. But the book also gives us some clues about the staff who had an accident and returned to work.

The railway companies – in common with most, if not all, industrial concerns of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries rarely bore the full cost of occupational accidents. Society – whether through family or community of the injured worker – frequently paid for treatment or care, and then lived with the consequences. This might mean reduced ability to earn and resultant financial difficulties. Nevertheless, the companies saw it as part of their paternalism that they made some provision, however restricted, for injured workers – whether through replacement limbs or by finding new roles suited to the circumstances the employee now found themselves in. Typically this was lighter work – and for an appropriate level of pay, which meant a reduction.

Some of these cases show through the information in the GER’s benevolent fund book. For example, on 18 February 1915 A Balls applied for £10.10.0 (around £800 in today’s prices) as the cost of an artificial leg, replacing one lost in an accident on 3 December 1895. Clearly some workers lived with their disabilities for quite some time after their accident. Coping with any bodily change was only one part of the equation; those affected also needed to pay the bills. So, in Balls’ application for a new limb, his role was detailed: he was a ticket collector, based at Temple Mills station in Essex. Whilst it is possible that he had lost his leg in the same role 20 years before, it seems unlikely. More probable is that he had been employed in a more physical occupation at the time of the accident, and then unable to continue after the loss of the leg, he had been moved across to the ticket collector role.

This is definitely the case for Urias Drayton, who lost a leg on 8 December 1909. By 15 October 1914, when he applied for £10 for the cost of a new leg, he was listed as based at King’s Lynn in Norfolk. Importantly, both his occupations on the Great Eastern were listed in the relevant column: ‘Gateman (was Pilotman)’. As a pilotman Drayton would have joined locomotive crews, to ‘guide’ them over sections of the railway where particular restrictions were in place – helpfully depicted in this c.1956 British Transport Films instructional film, particularly at start, 7 minutes 45 to 10 minutes and from 16 minutes. After the accident, it appears he was found a new role as a gateman: someone responsible for opening and closing the gates at level crossings.

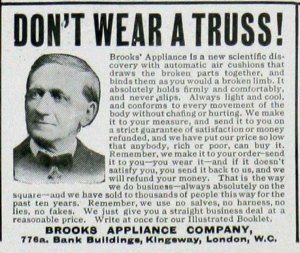

Source: Grace’s Guides.

Not all injuries were so fundamental, of course. In some cases employees appear to have continued in their existing role whilst carrying an injury. Goods guard Ransom suffered a rupture at Peterborough on 2 April 1918; at the benevolent fund committee meeting on 3 May 1918 he was awarded 5 shillings for a truss. However, at the meeting of 19 May 1922 another goods guard Ransom of Peterborough – presumably the same man – was awarded £2.2.6 for a Brooks appliance, a type of truss, for a rupture suffered on 1 December 1913. This might have been the original injury, never healed and with which Ransom had worked for nearly 10 years, supported with a truss for at least part of that time.

The benevolent fund book wasn’t designed to answer the sorts of questions we have of it now – it was a working document, a record of the decisions made and money disbursed. So, in many cases the links we’d like to make can’t be shown definitely. However, there are often connections which are reasonably strong – sufficiently so that we might be as certain as we can that they are the same person, or that they had occupied an earlier role before their accident. It can help us understand what happened to workers and how they lived their lives after the accident.